Banking-on-a-Headache

“Every company will be a fintech company” proclaimed Angela Strange in an article earlier this year, with non-financial brands enabled by a new wave of embedded finance platforms: the “AWS for Fintech”. This quote and projection have done the rounds (understandably, as it’s a great piece and one I certainly agree with). But it also got me thinking ahead of a relevant (and timely) AWS webinar I’m participating in with Francesco, the CEO of Open Banking platform Truelayer (a Mouro Capital portfolio company) and Nigel Verdon, CEO of Banking-as-a-Service provider Railsbank: two infrastructure businesses, both enabling embedded finance, both with a modern tech stack and APIs, and yet with very different approaches and business models.

Despite an explosion of interest in these new platforms, all too often the narrative is muddled. Open banking, banking-as-a-service, banking platforms, open finance, platform banking, banking-as-a-platform (I could go on) – they’re often spoken of within the same breath. Throw in geographic quirks and different licensing regimes, and the complexity grows further. Confused? You’re not the only one.

This is my attempt to unpick some of the complexity and talk through how we think about the market at Mouro Capital. It’s not the only way to categorise the space, and some companies almost certainly fall between the gaps, but it’s here to discuss and debate and it has certainly proven helpful for us internally when framing the industry.

Firstly, let’s get an important definitional assumption out of the way…

“Bank” vs “banking”. Both are regulatory ‘sensitive’ words – you can’t call yourself a bank for instance if you’re not regulated as one. However, what a bank is, and what a bank does are two different things, hence there are companies that describe themselves as providers of ‘Open Banking’ and ‘Banking-as-a-Service’, but they don’t necessarily have a bank license.

The definition of bank is perhaps the most straightforward: it’s a financial institution regulated and authorised to accept customer deposits and create credit by lending out those deposits. It may offer other payment activities and financial services, but it is the protected deposit-taking and credit creation activities that make it a bank.

The act of banking however is more complex. Technically, it’s “the business activity of a bank”. But as mentioned, these activities are generally broader than just deposit taking. And in Europe in particular, a number of activities that were historically the privilege of only banks, are increasingly being opened up. Non-banks for instance can now get direct access to the Bank of England with their own settlement accounts, and eMoney institutions can issue payment accounts and IBANs for customers to hold, send and receive funds.

Why does this matter?

Well, for the purpose of this segmentation I’ve taken the stance that you don’t need to have a ‘bank’ license to necessarily provide ‘banking’ services (he braces). This may seem like semantics (and some people will disagree), but it’s important as I feel it’s at the heart of some of the confusion between the different business models.

So how do we segment the banking infrastructure universe?

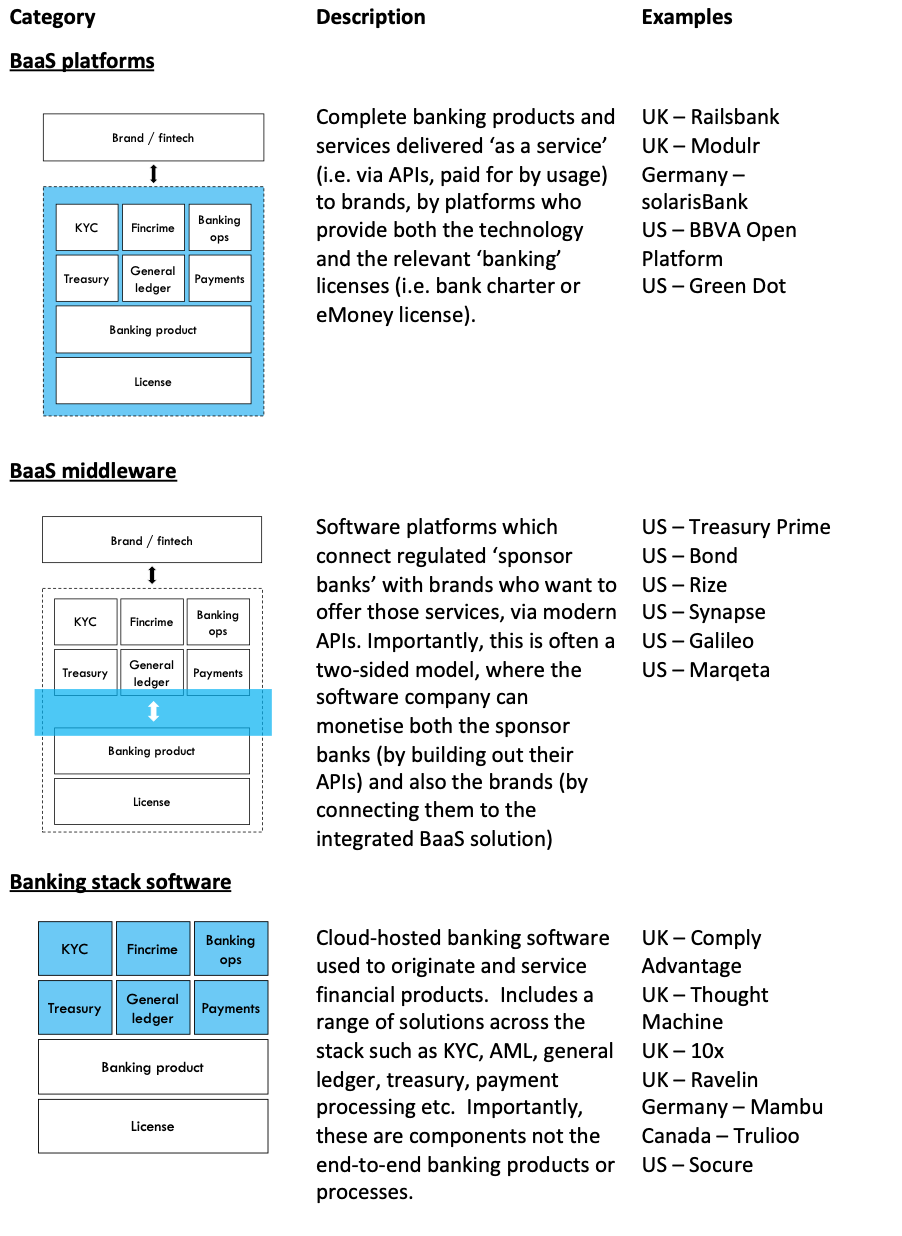

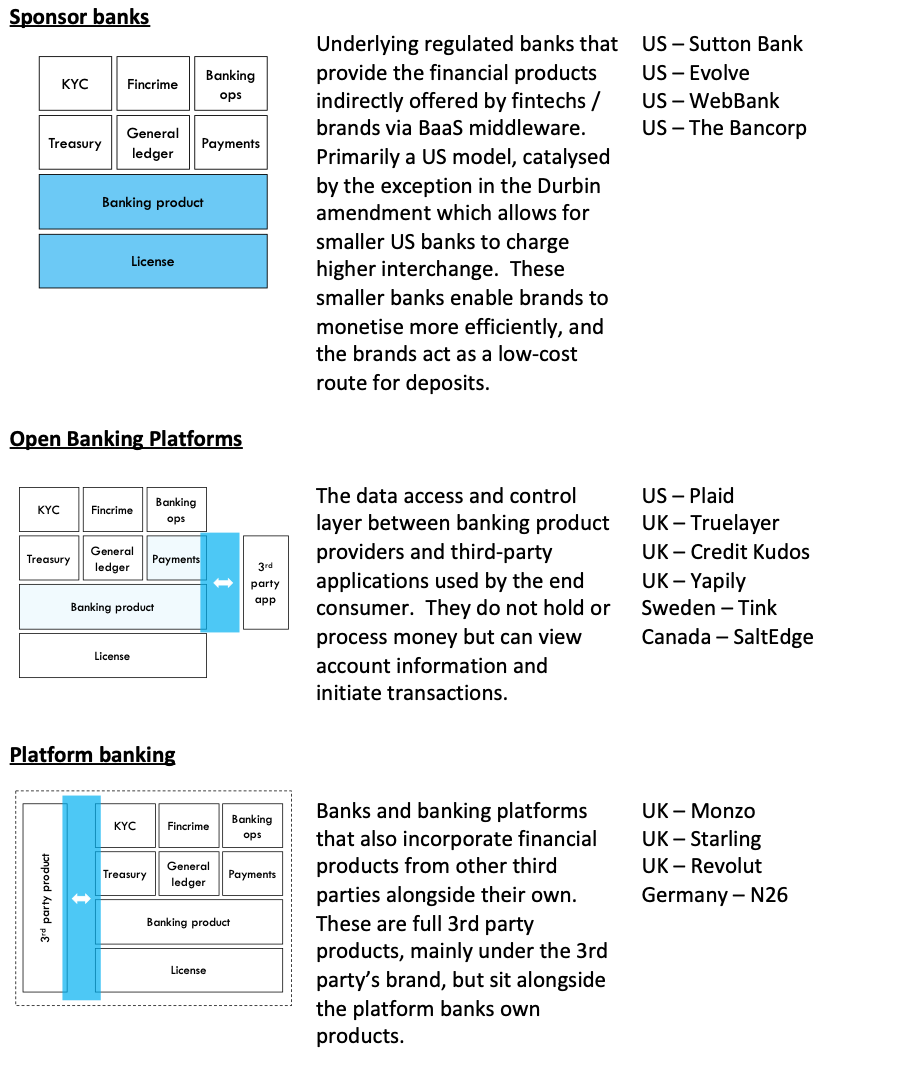

I’ve attempted to group different providers and solutions into six different categories, with the aim of being as mutually exclusive as possible. Inevitably, there are several providers who fit into multiple buckets as they have a suite of offerings (e.g. Galileo provides standalone card issuing as well as broader BaaS middleware), but generally the different categories, their business models and their products should be quite distinct.

Still not clear? Well, let’s pull out a few examples for comparison…

How do BaaS platforms and Open Banking Platforms differ?

Banking-as-a-Service platforms deliver the underlying financial products and services (for instance, deposit taking accounts with payments in/out) to brands who incorporate this into their own offering using the BaaS platform’s license. SolarisBank for instance provides the ‘checking account’ functionality for crypto-banking startup Bitwala.

In comparison, Open Banking platforms allow third parties to access data from existing checking accounts at other banks and initiate payments from them. Crucially they only provide visibility and initiation of existing products, rather than create the financial products and services themselves. Truelayer for instance powers Revolut’s open banking features, which allow customers to view their other bank accounts within the Revolut app, and to initiate payments from those accounts.

Why would a company use BaaS middleware and a Sponsor Bank over a full BaaS platform?

This is particularly interesting and most relevant for the US market…

Firstly, getting a US bank charter is HARD. As a result, the banking infrastructure platforms in the US have instead largely opted for a partnering model with smaller regional US banks who can provide the products and the license. There are exceptions (incumbent BBVA’s Open Platform for instance, which utilises the existing BBVA banking charter), but the majority of platform providers have had to pursue the middleware route instead. These smaller banks do however also provide an interesting additional revenue opportunity for middleware providers. Many of these banks are hindered by a legacy banking stack and are yet to re-platform so are opting to work with BaaS middleware providers such as Treasury Prime who are building the required APIs and connections for them to more easily integrate third party vendors and fintechs.

A second reason for using BaaS middleware providers plus a Sponsor Bank is revenue model: the Durbin Amendment exception for smaller banks (which allows them to charge higher interchange fees than larger banks) means that interchange is still a lucrative opportunity for fintechs and brands who issue a debit card with these smaller sponsor banks. The opportunity only exists however for banks with less than $10bn in assets, so for brands and fintechs where interchange is important, partnering with a smaller banks makes more economic sense, and the BaaS middleware providers help enable them to do this.

And so, what do we believe will be the winning model?

This is the (multi-)million dollar question! And unfortunately, there isn’t a nice simple answer. Given the geographic nuances, we believe certain models will be more successful in certain geographies and that it isn’t a winner-takes-all scenario.

In Europe, Open Banking Platforms are being supported by extremely strong regulatory tailwinds as European regulators are keen to stimulate competition and encourage innovation. We expect payment initiation in particular to be a huge growth space as the dominance of the card networks is challenged, and as payments become increasingly embedded across platforms. With a strong team, great product and early-mover advantage, we believe our portfolio company Truelayer is well positioned to capture this opportunity.

In the US, for those wanting to build out embedded or standalone banking products and services, the challenging regulatory environment, fragmented bank market structure and interchange opportunity present a really big opportunity for BaaS middleware providers. Unlike Europe with its passporting regime, greater openness to new banks and eMoney regulations, the barriers for most brands and fintechs in the US will be just too high without the assistance of BaaS providers. And for smaller community banks, the middleware platforms are the fastest and potentially lowest cost route to modernising and interfacing with third party vendors and fintechs.

We’re on the look out for top teams tackling this problem space, so if that’s you, please get in touch!